Money is anything that people will accept as payment in exchange for goods or services.

The earliest forms of money were used to create a system of value so that people could compare items they wanted to exchange. This system of value was used for more than just buying or selling things — it became a marker of status, a characteristic that money still has today.

Eventually, someone came up with the idea of using precious metals (gold and silver or their alloys) as money. Beginning in Mesopotamia and Egypt around 4500 years ago, gold and silver began to be traded in the form of metal bars or bits of wire. The next big step occurred when little round lumps of electrum (a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver) began to be issued to a standard set of weights and marked by the issuer. These became the first coins.

Paper currency was the next major step in the evolution of money. Appearing some time during the 8th century in China, paper money has become the most common form of currency in use today. The possible exception to this is the latest innovation in currency: electronic money.

Use the links in the Quick Navigation below to explore the History of Money Virtual Exhibit. 360° VR Tour, and other information on this page.

- History of Money Virtual Exhibit

- History of Money 360° VR Tour

- Ancients: The World’s First Coins

- Traditional: Money Comes in All Forms

- Medieval: Aftermath of Rome’s Fall

- Modern: Rise of the Press

- Paper Money: A Convenient Medium

- Alternative: Money in a Pinch

- U.S. Paper Money: Economic Expansion

- Explore More Virtual Exhibits

Types of Money

Ancients: The World’s First Coins

Coinage—in the form of small metal discs, ingots or replicas of metal tools marked with information about their value or origin—first appeared in Asia Minor, India and China during the 1st millennium BC.

From these areas originated the three major monetary traditions (Greek, Indian and Chinese) that influence our modern ideas of how money should look and how it should be used.

Coinage was invented in the ancient kingdom of Lydia during the 7th century BC, in what is today central Turkey. The idea was quickly adopted by the Greeks and soon nearly every Greek city and colony from southern France to the northern shores of the Black Sea began to produce their own coins.

The Romans adopted coinage from the Greeks during the 3rd century BC and developed the first fully monetized society. Money was used in the daily transactions of the majority of Romans, creating a huge demand for coins.

The Romans took advantage of this demand and became masters at using coins as propaganda. They developed a “language” of abbreviations and symbols on coinage that is still used today.

Lydian Kingdom, c. 600 B.C. Electrum Trite

Lydian Kingdom, c. 600 B.C. Electrum Trite. Obverse: Lion head with star above. Reverse: Incuse punchmark.

Roman Imperatorial, Julius Caesar, 49-44 BC Silver Denarius

Roman Imperatorial, Julius Caesar, 49-44 B.C. Silver Denarius. Obverse: Elephant walking, trampling snake. Reverse: Priestly implements – simpulum, ax and apex.

Greece, Macedon, 359-336 B.C. Silver Tetradrachm

Obverse: Head of Zeus right. Reverse: Naked youth riding horse right with palm branch in hand. This coin celebrates the victory of Philip’s horse in the Olympic Games.

Traditional: Money Comes in All Forms

Money is anything that people will accept as payment in exchange for other goods.

It has had many uses over the ages, beyond its original development for purposes of long distance trade and military power. Whatever people use as a medium of exchange for goods or services is considered to be a form of money.

Money can also be a means of storing or accumulating wealth—in some cultures, some “money” has a purely ceremonial or prestige purpose in which the value of the object rests not in what it can buy, but what it represents.

Money creates a standard of value, simplifying trade.

Many cultures have gotten along without money altogether. Other cultures have used diverse materials such as rocks, shells, feathers and teeth.

More commonly, domesticated animals and metal ingots of various shapes and sizes have been used as money.

Traditional money has taken many forms but they all share certain characteristics in common. These characteristics are portability, durability, distinctive appearance and difficulty to counterfeit.

Indonesia, ND, Cowry Shells

Cowry shells have a long history of use as currency beginning in China. These shells originate in the Indian Ocean and were used in many of its bordering lands. These shells are holed in order to be strung.

Northeast North America, 17th Century, Beaver Pelt

Beaver pelts became a valuable trade item and form of currency starting in the 17th century as the European demand for the attractive and waterproof pelts grew.

Uganda, 19th Century, Glass

Venice manufactured multicolored glass beads such as these for centuries for use in trade in Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Medieval: Aftermath of Rome’s Fall

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, cities and towns shrank or disappeared altogether. Long-distance trade and a sophisticated monetized economy were replaced by barter and an agricultural subsistence economy. These changes are reflected in coinage.

The Western Roman Empire was replaced by a patchwork of barbarian kingdoms, isolated domains of Roman landlords and simple chaos. Money became scarce and was increasingly limited to one of two denominations in gold, except for in Italy, where a monetized economy survived due to the proximity of the Eastern Roman Empire.

Over the course of the 7th century, conditions began to settle down as the barbarian tribes formed permanent territorial kingdoms. The economy began to revive and coinage was struck in greater numbers.

As Western Europe recovered, limited coinages of gold fractions were replaced by silver “pennies” based on the Roman denarius—these coins became the basis for the monetary system introduced by Charlemagne.

The Eastern Roman Empire had troubles of its own. After a short military and economic revival in the 6th century, the empire was faced with a series of devastating wars with the Sassanid Persian Empire based in Iraq and Iran.

The Byzantines emerged victorious just as the Arabs under the prophet Mohammed erupted from southern Arabia with their new religion, Islam. The Arabs were able to defeat the weakened Byzantines and Sassanids, creating a new empire (the Caliphate), which spread from Spain to Afghanistan and beyond.

The Caliphate developed its own coinage, in keeping with Islam beliefs, which replaced its Byzantine and Sassanid predecessors as the standard trade coinage of western and central Asia.

Italy, Pavia, Henry II, 1004-1024, Silver Denaro

Italy, Pavia, Henry II, 1004-1024, Silver Denaro. Obverse: H RIC N (in shape of cross) / AVGVSTVS CE. Reverse: PAPIR / IMPERATOR

Visigothic Kingdom (Spain), Sisebut, 612-621. Gold Tremissis

Visigothic Kingdom (Spain), Sisebut, 612-621. Gold Tremissis, Emerita Mint. Obverse: +SISEBVTVS REX, Sisebut bust facing. Reverse: +EMERITA PIVS, Sisebut bust facing.

England, London, Edward II, 1307-1327, Silver Penny

England, London, Edward II, 1307-1327, Silver Penny. Obverse: EDWAR ANGL DNS HYB, Edward II facing within circle. Reverse: CIVITAS LONDON, cross with pellets

Modern: Rise of The Press

Modern European coinage begins at the end of the 15th century with the discovery of extensive new sources of bullion in the New World and in central Europe, starting an economic boom and introducing new, larger denominations of money to handle the increased volume of trade.

Machines such as the drop press, screw press, rocker press and roller press were invented to replace the hand-held hammer and dies, increasing speed and precision in coin production.

The introduction of steam presses in the early 19th century allowed for further progress in the minting process. These advances in technology resulted in the coins of today—machine struck, with perfectly round, milled edges, each an almost exact copy of the next.

These advances also set the stage for the adoption of Western concepts of currency worldwide.

U.S. Indian Head Eagle, Gold, 1912 S

Designed by Augustus St. Gaudens. Obverse: Liberty head left in feathered headdress, 13 stars above; LIBERTY on headdress band, 1912 below. Reverse: Eagle left, on fasces with olive branch; UNITED STATES OF AMERICA around, IN / GOD WE / TRUST in left field, E / PLURIBUS / UNUM in right field, TEN DOLLARS below.

Austria, Vienna, Maria Theresa, 1780, Silver Thaler Restrike

Visigothic Kingdom (Spain), Sisebut, 612-621. Gold Tremissis, Emerita Mint. Obverse: +SISEBVTVS REX, Sisebut bust facing. Reverse: +EMERITA PIVS, Sisebut bust facing.

Great Britain, Victoria, 1889, Gold Sovereign

England, London, Edward II, 1307-1327, Silver Penny. Obverse: EDWAR ANGL DNS HYB, Edward II facing within circle. Reverse: CIVITAS LONDON, cross with pellets

Paper Money: A Convenient Medium

Paper money was invented by the Chinese in the 7th century as way of simplifying large monetary transactions; it is a lot easier to handle than thousands of copper coins. The Chinese used paper money for centuries before Europeans began to use it during the 17th century.

The first Europeans were the Swedes, who developed paper money for reasons similar to those of the Chinese—the Swedes had an abundance of copper coinage that was difficult to use due to its weight and bulk.

By the end of the 18th century, paper currency was in use throughout most of Europe and its colonies.

Paper money developed in two forms: Drafts, which are receipts for value held on account; and Bills, which were issued with a promise to convert to “real” money, i.e. coins with value based on their metallic content.

The value of paper money before the middle of the 20th century was dependent on what it could be exchanged for—paper money had no intrinsic value of its own.

Thus, most paper currency specified that it was exchangeable at a location such as the Treasurer’s office, or a specific bank, for a specified amount of silver or gold coinage.

Modern paper money is rarely backed in this way—most world paper money is now backed simply by the issuing government’s promise to accept it in payment.

Paper money has become an increasingly important part of the money supply, moving from a poor substitute for coinage to the mainstay of modern economies over the last 150 years.

such as the drop press, screw press, rocker press and roller press were invented to replace the hand-held hammer and dies, increasing speed and precision in coin production.

The introduction of steam presses in the early 19th century allowed for further progress in the minting process. These advances in technology resulted in the coins of today—machine struck, with perfectly round, milled edges, each an almost exact copy of the next.

These advances also set the stage for the adoption of Western concepts of currency worldwide.

New Zealand, $5 Polymer Note, 1999

Front: Mount Everest to left, Sir Edmund Hilary, first to climb Everest. Back: Hoiho (Yellow-eyed penguin)

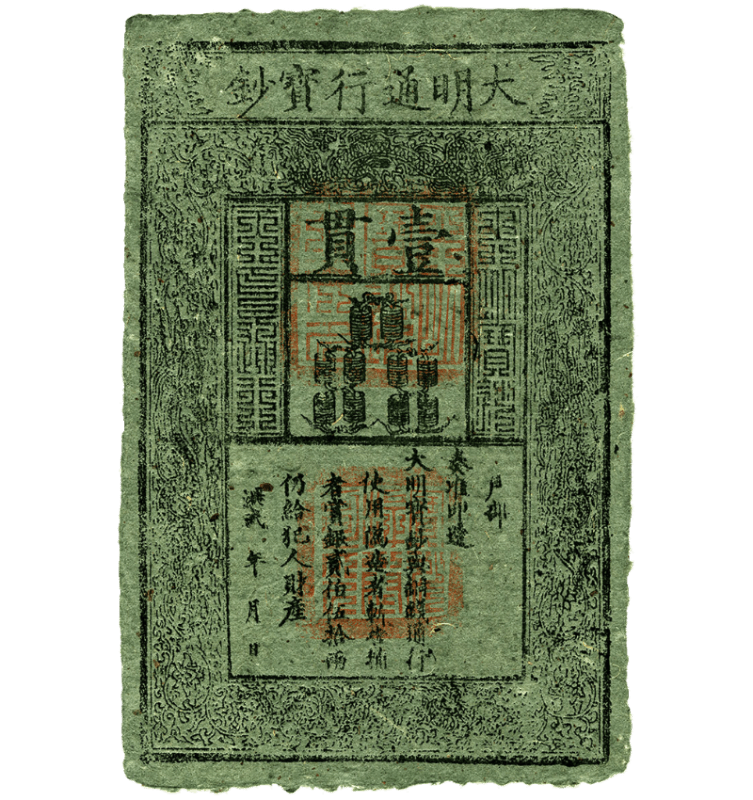

China, Ming Dynasty, 1 Kuan

“Great Ming Circulating Treasure Note,” 1368-1399, Mulberry Bark. An example of the earliest surviving paper money issue in the world, this note was worth 1,000 cash coins, as depicted on the note by the ten “strings” each of 100 coins.

Macedonia, 50 Denari, 2001

Front: Archangel Gabriel facing right. Back: Image of the Byzantine Follis.

Alternative: Money in a Pinch

Alternative and emergency money is created during economic hard times in place of regular coins or paper money.

Wars, recessions and natural disasters may result in the issuance of emergency currency. This currency is most often issued by local authorities, merchants or private individuals when money issued by the government becomes scarce or unavailable due to hoarding or lack of supply.

Today, this type of occurrence is rare and usually occurs only in more remote areas of the country, but in the era of bullion coinage, when a dollar was composed of just under a dollar’s worth of gold or silver, and paper currency was a substitute for “real” money, it was common for coinage to disappear from circulation, creating a crisis for merchants.

In the United States there was a severe recession in 1858, a panic in 1907 and a depression in the 1890s. The Civil War played havoc with the economy, and other times of hardship have plagued us every 10 to 20 years throughout our history.

Emergency coinage and paper fractional notes were used on many occasions, most famously during the “Hard Times” period of the 1830s and during the Civil War, when merchants issued tokens and paper scrip to replace the small change that had disappeared from circulation.

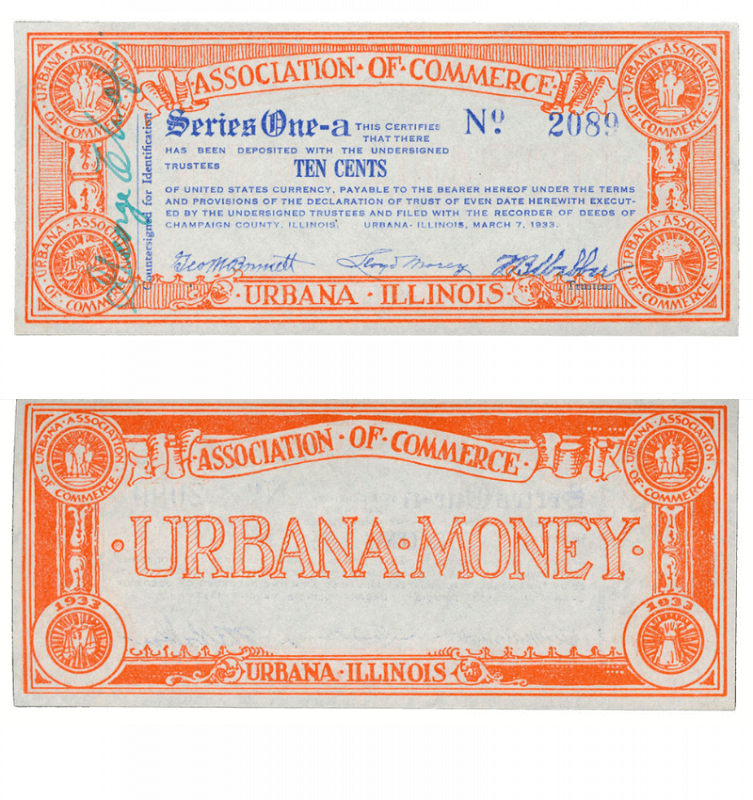

Urbana. IL, 10 Cent Scrip, Urbana Association of Commerce, March 7, 1933

A typical example of scrip issued by local merchants’ associations and backed by money deposited with the trustees of the association. This scrip intended to ensure that business could remain open in spite of the shortage of small change caused by bank closures.

Westphalia, 1 Billion Mark*, 1923, Silvered-Bronze

Obverse: Bust of Baron vom Stein left; MINISTER VOM STEIN DEUTSCHLANDS FUHRER IN SCHWERER ZEIT 1757-1831 (Germany’s leader in more serious times) Reverse: Rearing horse of Westphalia; NOTGELD DER PROVINZ WESTFALEN / 1923 around 1 / Billion / MK. in field. *In German 1 Billion = 1 Trillion U.S.

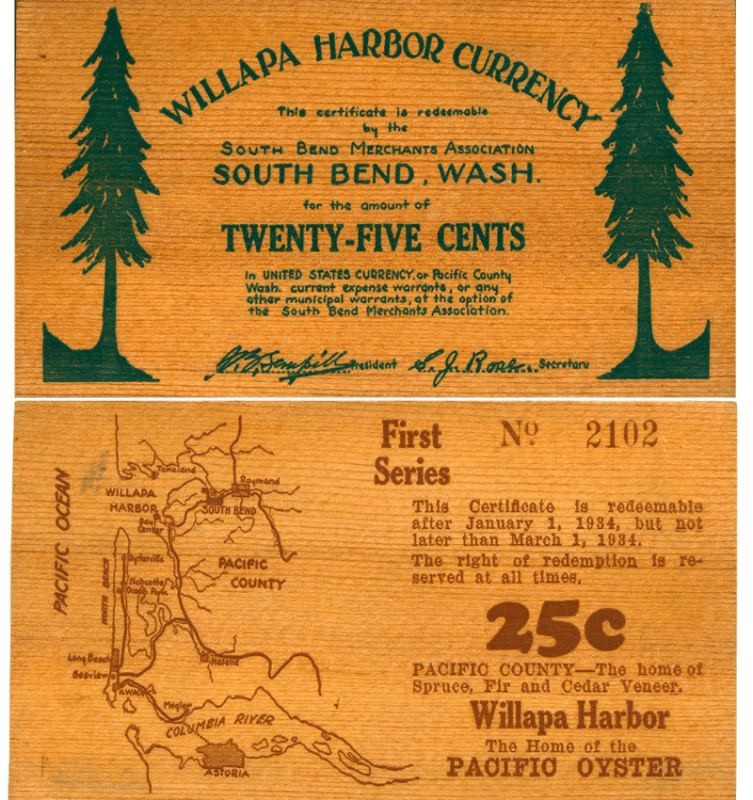

South Bend, WA, 25 Cents Willapa Harbor Currency, South Bend Merchant’s Association

Redeemable after 1/1/1934. Wood veneer. Issued by South Bend Merchant’s Association, this currency was made from wood veneer, the major product of Pacific County, WA. It was produced as a way of raising money from tourists and collectors than to be used as currency.

U.S. Paper Money: Economic Expansion

Paper money has a unique place in the history of the United States. The lack of bullion experienced by the British colonies in North America created an ideal setting for the first authorized government-backed issue of paper money in the western world.

In 1690, the Massachusetts Bay Colony approved the issuance of the first paper money in North America, and the first to be issued directly by a government in the West. Other colonies followed Massachusetts’ lead until paper money became common in the colonies, and was mostly successful, despite attempts by the British government to suppress its use.

The American Revolution witnessed a vast expansion in the issue of paper money by provisional state governments as well as the new Continental Congress as they attempted to cover the costs of the war.

Over-issuance caused the collapse of the currency so that by the end of the Revolution, the American public had lost confidence in paper money. Continental paper was eventually redeemed at one cent on the dollar, three decades after it was issued.

In 1789, the Constitution prevented the individual states from issuing paper money and the Federal government was reluctant to issue paper money due to past experience.

Thus, Federal treasury notes were only issued during emergencies such as the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War. However, the continued lack of sufficient silver or gold coinage made paper currency necessary for the economy to grow. Banks chartered by individual states and corporations provided the answer by issuing paper money, now known as obsolete notes.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the Federal Treasury realized that a new paper money system was needed. New methods for raising money were established, including the creation of a permanent Federal system of paper currency.

Congress authorized the issuance of regular circulating paper money in 1861 for the first time since the Revolution. Known as “demand notes,” these were redeemable in hard cash on demand.

In 1862, demand notes were replaced by Legal Tender notes, and, in 1863, by Compound Interest Treasury notes. These notes became known as “greenbacks” due to their green color.

In 1863, the National Banking Act was introduced to replace the obsolete state-chartered banknotes with a reliable, standardized series of notes issued by national banks backed by government bonds deposited with the Treasury.

By the second half of the 19th century, the United States was producing the finest and most stable bank notes in the world. American paper money became the model for many countries, and American concepts of how paper money should look became the accepted standard for most of the world.

Garfield National Bank of the City of New York, $100, 12/15/1881

Charter #2589, BEP serial #A447137, Bank Serial #1822. Front: Two vignettes — Commodore Oliver Perry during the Battle of Lake Erie at left, Liberty seated by fasces. Back: Vignette of Thomas Jefferson presenting the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Congress.

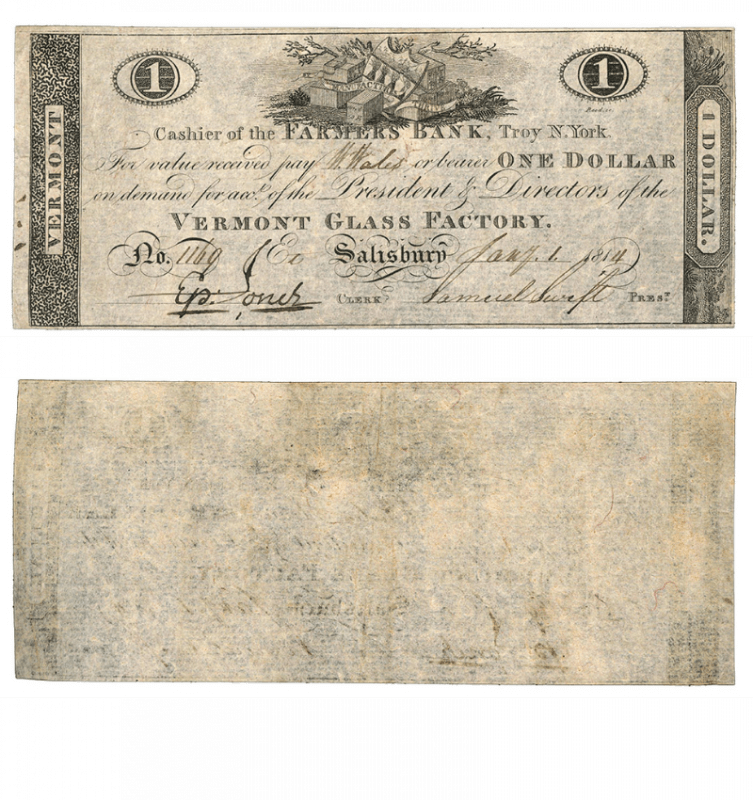

1 Dollar, Vermont Glass Factory of Salisbury, Payable by the Farmers Bank, Troy, NY, Jan. 1, 1814

Uniface: Vignette at center, Shield of arms with boxes around; BY MANUFACTURES WE THRIVE on ribbon.

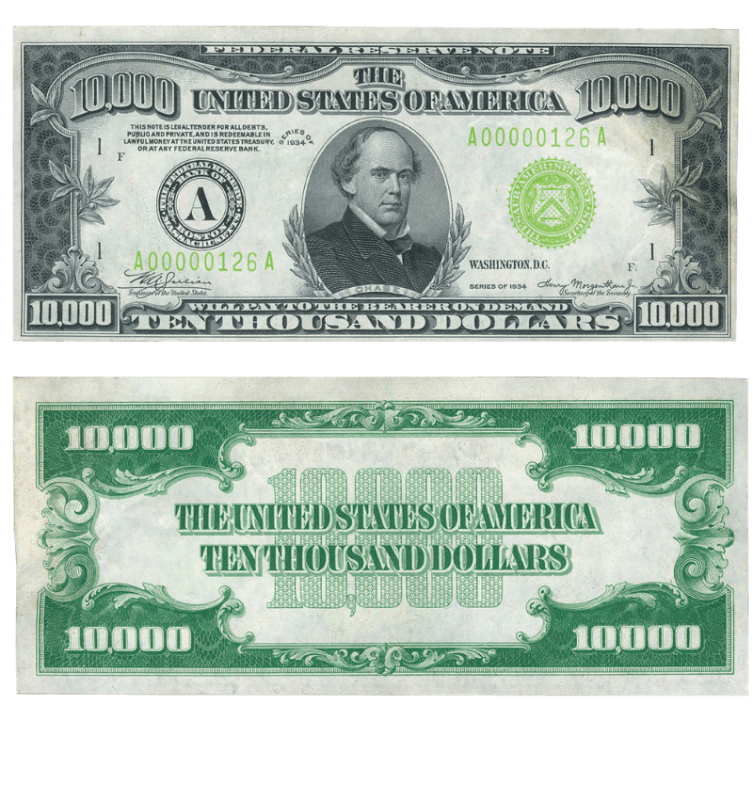

$10,000 Federal Reserve Note, Series 1934, Boston

Front: Treasury Secretary and Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase. Back: Denomination and design.