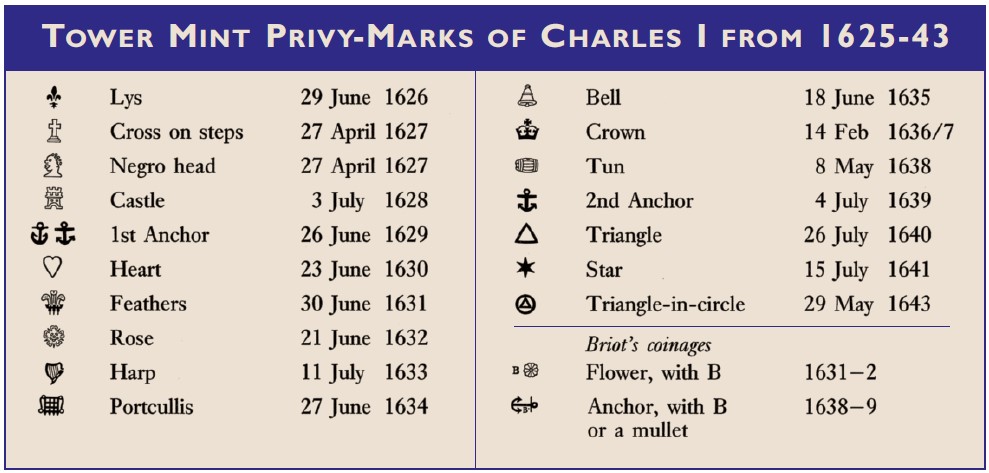

At the beginning of the Civil Wars, almost all English coins were struck by hand (“hammered” coins), except for a few produced by Nicholas Briot, who used rolling presses. During the Commonwealth, steps were taken to begin production of milled coinage and, by 1663, the Royal Mint converted to mechanized coinage once and for all, using screw presses and Peter Blondeau’s secret machinery for creating a high quality, lettered-edge on the coins.

The English Monetary System of Charles I20 shillings (s) = 1 pound (£) Coin DenominationsGold Silver Copper |

|

|