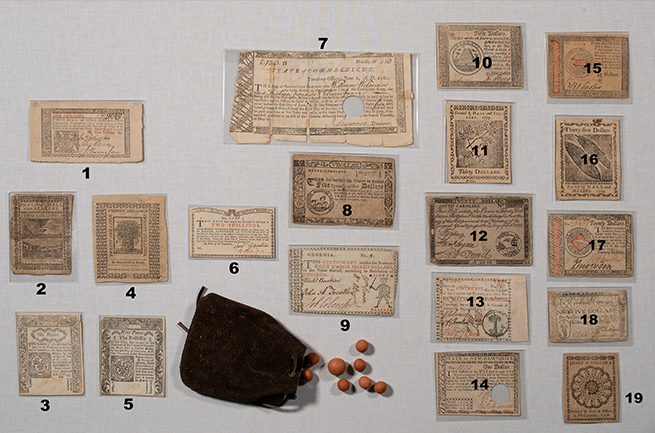

At first, patriotism and confidence insured the success of the notes but, as the war wore on and more and more notes were printed, they began to lose their value. By late 1777 the Continental dollar had begun to lose its value, in part due to British counterfeiting of Continental notes. In April 1780, when Continental notes ceased to circulate, the exchange rate was $40 in paper for $1 in silver or gold. The situation was worse for state currencies. Eventually, the American people refused to accept the notes and phrases such as “Not worth a Continental” became common. Continental currency was finally demonetized between 1790 and 1798 when it became exchangeable for U.S. Treasury bonds at the rate of 1 cent to the dollar. The bonds did not mature until 1813.

This experience heavily influenced the writers of the Constitution; states were forbidden from issuing their own currency, and the national government would exclusively determine the denominations and forms of American money, creating a unified currency for the nation — simplifying trade between the former colonies. Private issues of scrip were not regulated, however, setting the stage for the obsolete banknote period from 1782 through 1866.

|