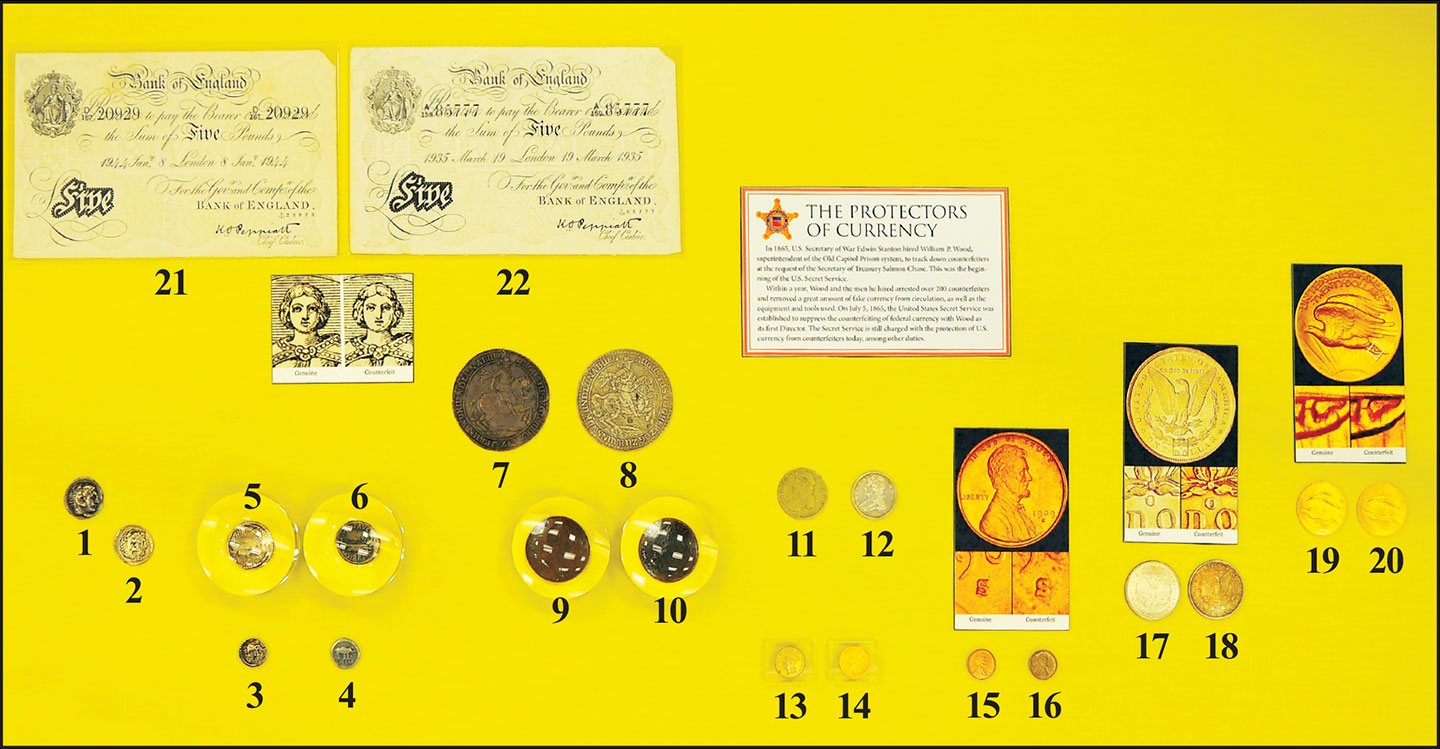

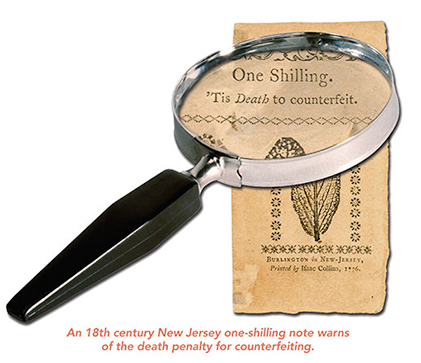

Most coin counterfeiting historically involved making struck or cast copies of circulating coins using base metals and coating them with a thin layer of silver or gold. Paper currency was easier to counterfeit and provided a vast opportunity for illicit profit. This type was the most common form until the 20th century. These counterfeits only have to pass as genuine once – from the counterfeiter to their victim – to be successful.

With the rise in popularity of coin collecting, a new form of counterfeiting developed beginning in the 16th century with individuals who were willing to “create” collectible Roman coins, called forgeries. Often they are of much higher quality than other counterfeits since they hace to pass close inspection by specialists. The best forgers use the same materials and manufacturing techniques as the original currency – sometimes altering genuine host coins and changing minor features, such as mint marks, to create a valuable “rarity.”

A subset of forgeries is modern copies of coins and notes for advertising and educational purposes. Before the passage of the Hobby Protection Act of 1973 there was no requirement that these “legitimate” copies be explicitly identifiable as replicas. The Act requires that all such items be clearly marked.

Other types of counterfeits are those created to undermine the economies of enemy nations. These are government-sponsored and typically focus on paper currency, using the most modern manufacturing techniques available – often making them nearly impossible to detect.

|

Click on the items in the case image below for an enhanced view