America Experiments in Paper

The first European emigrants to the New World faced an enormous challenge: surviving in an unfamiliar environment inhabited by exotic creatures, strange plants and potentially hostile natives. Civilization, as Europeans knew it, would have to be built from scratch. Money was the grease that kept the machinery of European civilization working.

To Europeans of the 16th and 17th centuries, “Money” was gold or silver. Coins were valuable not because the government declared them to be, but because they consisted of precious metal equivalent to their denomination. Unfortunately, precious metals were lacking on the eastern coast of North America.

The English colonists’ search for a convenient, secure and readily available form of money eventually led them to explore the possibility of paper currency. Colonial paper money began as receipts for commodities deposited at official warehouses. The most common “commodity notes” were issued for tobacco during the mid- to late-17th century in Virginia and Maryland.

The most common and well-known form of Colonial paper currency was the bill of credit. Bills of credit — notes issued by legislatures as credits against a colony’s treasury — could be used to pay taxes and other government obligations, and thus were widely accepted by merchants as well. The notes had no intrinsic value, as opposed to foreign gold or silver coins, where value was determined by weight, condition and conversion tables.

After Massachusetts paved the way for the use of paper money with its first issue in 1690, all of the colonies eventually began to issue their own paper currency. The notes were produced by colonial printers – the same people who printed books and newspapers. They were printed in large sheets which were then cut into individual notes and bound into books or sent as individual pieces to be hand numbered and signed.

|

|

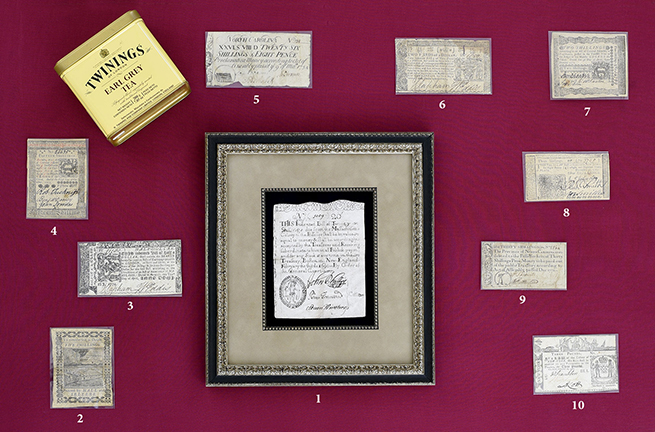

Click on the items in the case image below for an enhanced view