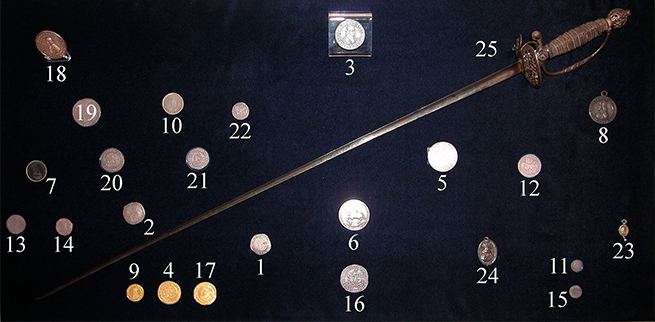

“The Protestant Religion, the Laws of England, the Liberty of Parliament”

– Motto for King Charles’ coinage during the English Civil War

Charles Stuart, the second son of James I and Anne of Denmark, was born in 1600. His small size (5’ 4”) and a slight stammer handicapped him throughout his life. In 1612, Charles became heir to the throne on the death of his brother, Prince Henry. He became king of England and Scotland in 1625. He was a devout family man and a firm believer in the idea of the divine right of kings (kings are appointed by God and, therefore, their actions are not subject to judgment by men).

This belief, combined with his stubbornness and careless spending, meant that Charles almost immediately ran into trouble with Parliament over money (Parliament had the power to create new taxes), made worse by the costs of war abroad. Charles’s marriage to Catholic Princess Henrietta Maria of France in 1625 was considered ominous by his Protestant subjects, especially since Catholic plots against Elizabeth I and James I were still vivid in the public memory, and because the Protestant cause was going badly in the Thirty Years War (1618-48) in Europe. Many feared he would reinstate Catholicism as England’s official religion and that he wanted to rule as an absolute monarch without Parliament.

Charles dismissed his fourth Parliament in 1629, thus beginning 11 years of personal rule without Parliamentary advice or new taxes. Charles’ decision was within the king’s royal prerogative, but it added to the problems he would later have when he had to recall Parliament. The king gained most of the income he needed by exploiting forest laws, forcing loans, selling monopolies, and collecting ship money (a tax demanded from towns to build naval warships). These measures made him very unpopular, especially in combination with the increasingly Puritan nobility’s dislike for Charles’ devoutly Catholic wife and her Catholic friends at the Royal court.

Charles’ attempt to impose a unified Anglican High Church liturgy and prayer book throughout Great Britain met with Scottish opposition and rebellion in 1637. He was forced to recall Parliament in order to raise money for an army to restore order, but the Short Parliament of April 1640, as it became known, questioned Charles’ reasons for war against the Scots. Parliament was dissolved within weeks, creating a financial and political crisis for the king.

Parliament was called again in November of 1640, and the king was forced to make concessions in order to obtain money. Unfortunately, the Irish uprising of October 1641 again raised tensions between the king and Parliament, and Parliament issued a Grand Remonstrance (list of grievances) repeating its grievances, impeached 12 bishops and attempted to impeach the Queen.

Charles then unsuccessfully attempted to arrest five members of Parliament responsible for the Grand Remonstrance. The result was the start of the English Civil Wars. Charles raised the Royal Standard at Nottingham in 1642, and called for his loyal subjects to support him against Parliament. After almost three years of warfare, Oliver Cromwell and his New Model Army crushed the Royalist army at Naseby in 1645. Charles then surrendered to Scottish forces in 1646, which, after not reaching an agreement with him, turned the king over to Parliament in 1647. Charles was put on trial for treason; the tribunal, by a vote of 68 to 67, found the king guilty and ordered his execution in 1649.

|