By Andy Dickes

ANA Money Museum highlights examples of the world’s oldest

existing notes.

No civilization has contributed more to the development of

numismatics than China; in fact, the word “cash” originally was used to

describe bronze coins with square center holes used during the Tang Dynasty

(A.D. 618-907). China’s most lasting innovation is paper money that was created

in the 7th century. Western civilization didn’t begin to follow the lead on

this practical concept until the 17th century.

The Chinese introduced “flying cash” during the Tang Dynasty

in the form of privately issued paper bills of credit. Early in the Song

Dynasty (960-1279 A.D.), circulating promissory notes were used to make up for

a shortage of copper for coins. Paper money as we know it debuted during the

Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), which issued “exchange certificates” without date

limitations. The Mongol Yuan Dynasty (1206-1367) banned coinage altogether,

relying on paper exclusively. This dependence on paper money was witnessed by

Italian explorer Marco Polo, who first reported its widespread use, to the

astonishment of the Western world.

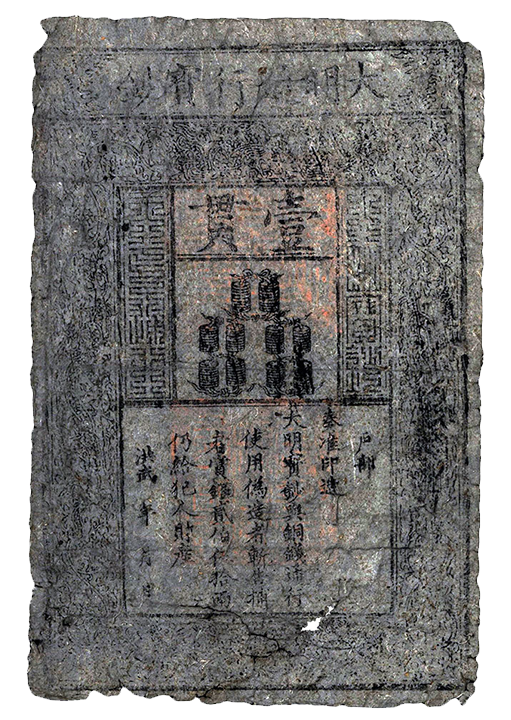

Some of the first surviving specimens of paper money date to

the 14th century at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), during the

reign of the Hongwu (or Hung-Wu) emperor from 1368 to 1398. These notes were

quite large (about 22.5 x 13.4cm) and made from mulberry bark. They were issued

in denominations of 100, 200, 300, 400, 500 and 1,000 cash. Later in Hongwu’s

reign, 5-, 6-, 7-, 8-, 9-, 10-, 20-, 30-, 40- and 50-cash notes also were

produced.

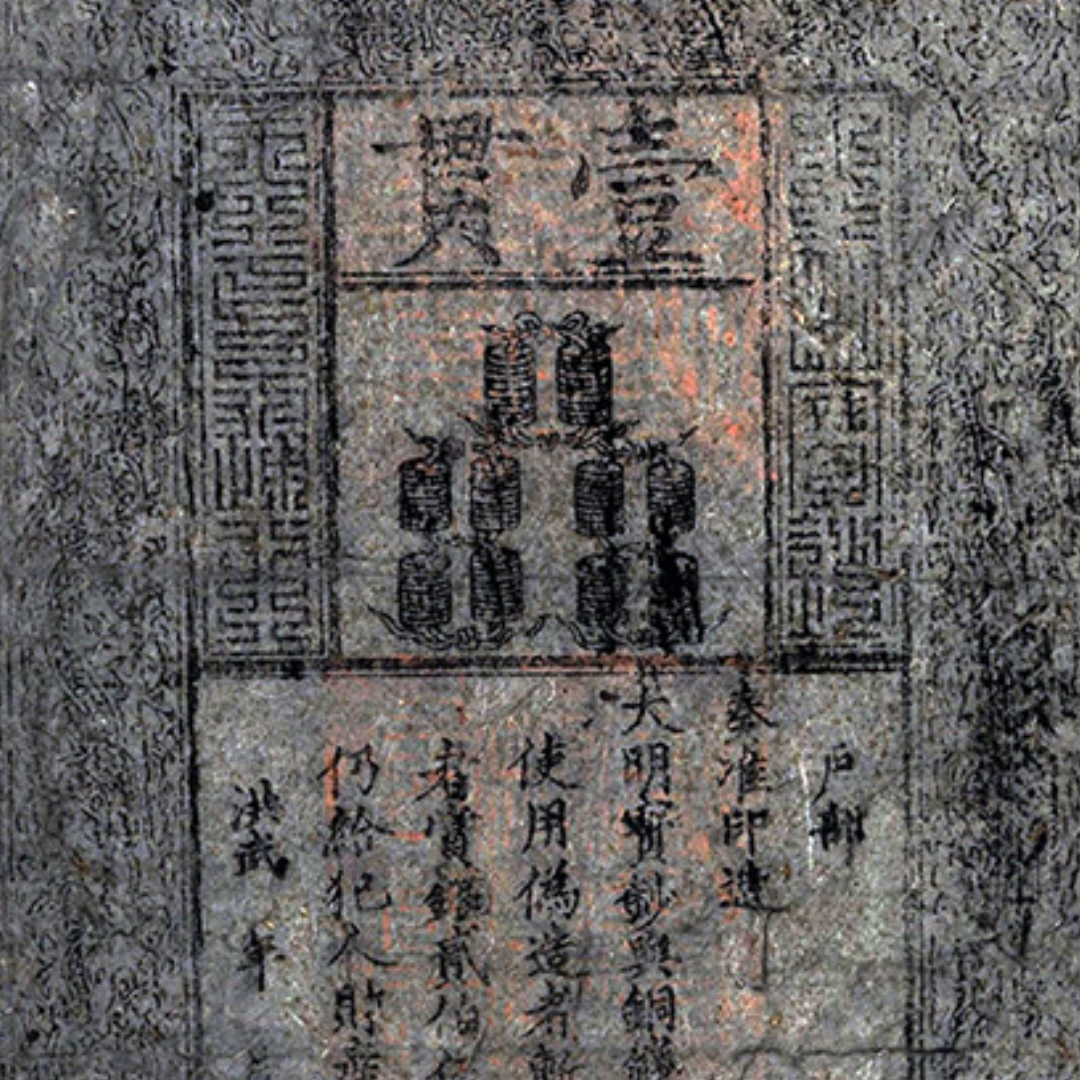

The Edward C. Rochette Money Museum features an authentic

1,000-cash (1-kuan) note in its “History of Money” exhibit. The design consists

of 10 strings of copper coins surrounded by geometric designs and Chinese

characters. Each string is composed of 100 copper coins, representing the note’s

value of 1,000 cash. Notes like the kuan were used for centuries alongside

strings of copper coins and large silver ingots.

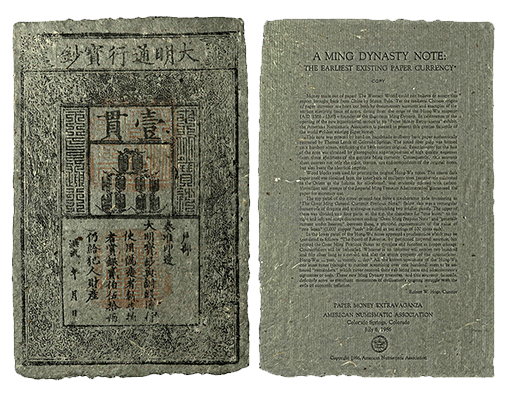

The Money Museum debuted a popular “Paper Money

Extravaganza” exhibit in 1986. To celebrate the opening of the display’s international

section, the ANA commissioned the production of a set of replica 1-kuan notes,

which were produced by Thomas Leech of Colorado Springs, Colorado, and made of

mulberry bark paper. The front design was photographically superimposed using

authentic examples. The back, which would normally bear a red government seal

and black stamp depicting 1 kuan, features a message from then-ANA curator

Robert W. Hoge:

Wood blocks were used for printing the original Hung-Wu

notes. The coarse dark paper itself was obtained from the inner bark of

mulberry trees (extensively cultivated in the Orient as the habitat for

silkworms), and evidently colored with carbon. Vermillion seal stamps of the Imperial

Ming Treasury Administration guaranteed the paper for monetary use.

The top panel of the notes printed face bore a six-character

title translating as “The Great Ming General Currency Precious Note.” Below

this was a rectangular framework of dragons and arabesques surrounding two smaller

panels. The upper of these was divided into four parts: at the top, the

characters for “one Kuan;” to the right and left, seal script characters reading

“Great Ming Precious Note” and “generally current under heaven;” between these,

a political representation of the value of “one kuan” (1,000 copper “cash”

bundled as ten strings of 100 coins each).

In the lower panel of the HungWu notes appeared a

proclamation which may be translated as follows: “The Board of Revenue, by

petitioned imperial sanction, has printed the Great Ming Precious Notes to circulate

and function as copper coinage. Counterfeiters will be beheaded. Whoever is an

informer will receive two hundred and fifty silver liang as a reward, and also

the entire property of the counterfeiter. HungWu: __ year, __ month, __ day.”

All the known specimens of the HungWu one kuan notes (thought to number something

over one hundred) seem to be unissued “remainders,” which never received their

validating dates and administrator’s signatures or seals. These rare Ming

Dynasty treasures, and this souvenir facsimile, definitely serve as trenchant mementoes

of civilization’s ongoing struggle with the evils of economic inflation.

An over-issuance of paper money created a problem that has

been repeated many times since: hyperinflation. The Ming Dynasty discontinued the

use of paper money in 1455, with initially disastrous results for trade. All

paper notes were ordered to be destroyed, and authentic examples are scarce; a

large bundle was discovered by foreign forces in Peking during the Boxer

Rebellion in 1900. Only in the 19th century was paper money reintroduced as

part of the Chinese currency system.

Pictured above: A 14th century Ming Dynasty 1-kuan note from the ANA collection. ANA# 1994.19.1

Photo credit: ANA Edward C. Rochette Money Museum

Pictured below: A replica 1-kuan note created for the ANA by Thomas Leech in 1986. Actual Size: 22.5 x 34cm.

Photo credit: ANA Edward C. Rochette Money Museum