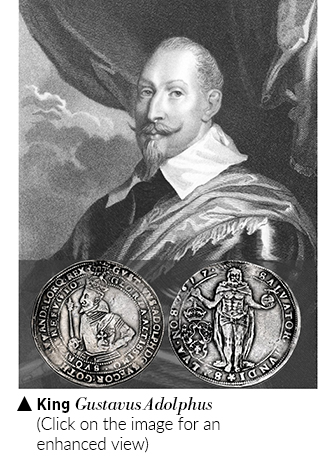

Thanks to the military prowess of King Gustavus Adolphus, Sweden – once a regional power – catapulted to the world stage during the 17th century. Known as the “father of modern warfare,” Adolphus is widely remembered as a hero of Protestantism, defending its cause in the Thirty Years War.

However, his prowess on the battlefield caused economic woes for his nation. During his reign (1611-1632), the European economy valued coins based on their alloy content and weight. Money, therefore, was literally worth its weight in gold, silver or copper. Practically speaking, nations needed access to these metals (commonly used for coinage) to produce a national currency. Those with insufficient quantities were forced to seek monetary substitutes such as furs, tobacco and even nails, as was the case in Colonial America.

While Sweden conquered the Baltic landscape, the region lacked significant sources of silver or gold. Already deficient in precious metals, the new stormaktstiden (Era of Great Power) required large amounts of coinage to maintain Sweden’s advantage through its mercenary armies, preferably in silver.

Therefore, Sweden had to get creative, and after consulting his economic experts, Adolphus decided to bank on copper. A crucial metal in warfare and critical for the production of canons, Sweden had the greatest and most numerous copper mines of Europe, supplying approximately two-thirds of the copper used on the continent, most of which was sold in exchange for silver.

In 1624, Sweden issued large quantities of small copper coins for domestic use, which thereby reduced copper exports. With less copper on the open market, Sweden hoped its main metallic export would rise in demand and value. However, the coins’ denominations were too small for larger markets. That role remained with the elusive silver, still required to pay mercenaries’ wages and conduct international transactions. The over production of copper coins eventually led to their depreciation in value, which negatively influenced the price of copper itself.

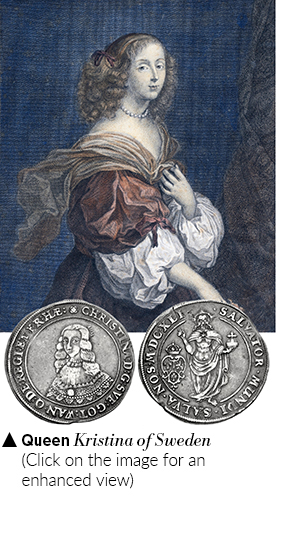

Unfortunately, Sweden’s economic woes did not die with King Gustavus Adolphus in 1632. Sweden, its copper and the struggling economy were left to his 7-year-old daughter, now Queen Christina, who would mature into a numismatist herself! His trusted prime minister, Count Axel Oxenstierna, acted as regent. Two years prior, Oxenstierna determined that the crown’s attempt to manipulate the copper market through coins was unsuccessful. On Oxenstierna’s recommendation, Christina’s government attempted to rectify copper’s ever-decreasing value, eventually fixing its exchange rate with silver in 1644. The government also established copper as the monetary standard, in contrast to all other nations that used silver or gold (and occasionally both, as the US attempted to do). A pragmatic choice considering Sweden’s massive supplies of copper, she also issued copper “coinage” denominated in dalers, equal to two-thirds the value of its contemporary, the silver riksdaler.

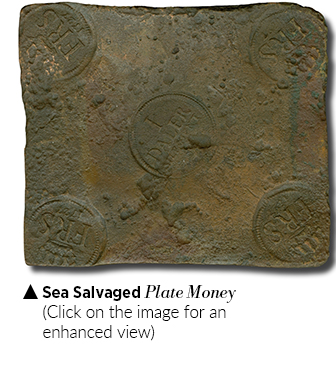

Her large copper lumps or “plates” ranged in weight from 378g (just under a pound) to a staggering 23.8kg (more than 53 pounds!), the largest coins ever minted at the time. Hammered into sheets of the necessary thickness, they were then cut to size with shears and stamped. Four corner stamps bore the ruler’s name or initials along with the year of issue, while the center one denoted denomination. The reverse is blank. The pieces themselves are works of art. Created by hand, each plate has a beautifully unique character.

Produced in denominations ranging from a half daler to 10 dalers, their production costs were far less than numerous small coins of equivalent value, they simplified copper exportation, and they relieved the Swedish economy’s dependence on imported silver. However, their notable size of 88.9mm square (3.5 in) to 317.5 by 673mm (12.5 by 26.5 in) made them incredibly cumbersome, and their inconvenience for everyday commerce proved unpopular. (Imagine having to use a horse to carry the copper necessary to… buy another horse!) Indeed, an account of a bank robbery in Stockholm relates that the thieves took all the money except for the plate coins. They were too heavy and not worth the effort! Despite their innate theft protection, the enormous 10 daler denomination was quickly discontinued in 1648 as too impractical, followed by the 8 daler in 1682.

While copper plate money was never popular, it was effective, largely due to the metal’s intrinsic value. However, the government formally abandoned the copper standard and discontinued plate money in November of 1766. The decision stated that “Plate money, being almost always unreliable in value with regard to silver, and also expensive as regards costs, apart from being cumbersome and difficult to store, is … no longer to be issued and gradually withdrawn by means of any measures so required.”

Virtually all pieces of the demonetized currency were melted down over subsequent years. (Copper was too useful to remain unused!) Of the roughly 11,000 surviving pieces, most specimens come from shipwrecks, particularly that of the Danish East India Company ship, Nicobar. After sinking off the coast of South Africa in 1783, its wreckage was discovered in 1987. Divers found 3,000 examples of plate money over four months – the biggest find of copper plate money in history.

*A note about the eccentric Queen Christina.

Queen Christina of Sweden, known for her intellectual pursuits and unconventional behavior, often scandalized the royal court with her love for learning and disregard of societal norms. Her decision to abdicate the throne in 1654 shocked Europe. Historically, it is attributed to her need for personal freedom, her frustration with the constraints of royalty, and her desire and eventual conversion to Catholicism. The former protestant Queen retired to Rome where she pursued her scholarly interests until her death.

Learn More The Money Museum Masterpiece Series: Riksdaler Plates